Learn about dengue fever, including symptoms, phases, diagnosis, and prevention tips. Stay informed to reduce risks and protect yourself from this illness.

Dengue Fever:

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne illness that has become a significant global health concern. It’s caused by the dengue virus, which is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito.

Key Points About Dengue Fever:

- Dengue viruses are spread to people through the bite of an infected Aedes species (Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus) mosquito. Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne illness that occurs in tropical and subtropical areas of the world.

- Belongs to family Flaviviradae

- Dengue is defined by a combination of ≥2 clinical findings in a febrile person who traveled to or lives in a dengueendemic area.

- Severe dengue is defined by dengue with any of the following symptoms: severe plasma leakage leading to shock or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress; severe bleeding; or severe organ impairment such as elevated transaminases ≥1,000 IU/L, impaired consciousness, or heart impairment.

- Dengue begins abruptly after a typical incubation period of 5–7 days, and the course follows 3 phases: febrile, critical, and convalescent.

Epidemiology:

Almost half of the world’s population, about 4 billion people, live in areas with a risk of dengue. Dengue is often a leading cause of illness in areas with risk. Dengue fever is most common in Southeast Asia, the western Pacific islands, Latin America, and Africa. However, the disease has been spreading to new areas, including local outbreaks in Europe and southern parts of the United States.

- Infection with one of the four dengue viruses will induce long-lived immunity for that specific virus.

- Because there are four dengue viruses, people can be infected with DENV multiple times in their life.

- Approximately 1 in 20 patients with dengue virus disease progress to develop severe, life-threatening disease called severe dengue.

The second infection with DENV is a risk factor for severe dengue.

Early clinical findings are nonspecific but require a high index of suspicion because recognizing early signs of shock and promptly initiating intensive supportive therapy can reduce risk of death among patients with severe dengue to <0.5%.

Pathogenesis:

Clinical Presentation:

Dengue virus infection presents a wide spectrum of manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe illness. Below are the key clinical aspects:

1. Asymptomatic to Symptomatic Cases:

- Approximately 1 in 4 dengue infections result in noticeable symptoms.

- Symptomatic cases typically manifest as a mild to moderate nonspecific acute febrile illness.

2. Common Clinical Features:

General Symptoms:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Rash

- Aches and pains

Diagnostic Indicators:

- Positive tourniquet test

- Leukopenia (low white blood cell count)

3. Warning Signs for Severe Dengue:

Patients with the following warning signs are at risk of developing severe dengue:

- Abdominal pain or tenderness

- Persistent vomiting

- Clinical fluid accumulation

- Mucosal bleeding

- Lethargy or restlessness

- Liver enlargement

4. Laboratory Findings:

- Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), and transaminitis (elevated liver enzymes) are common findings.

5. Secondary Infections:

- A secondary dengue infection often occurs within 18 months of the initial infection, potentially increasing the risk of severe disease due to antibody-dependent enhancement.

Diagnosis of Dengue:

Accurate diagnosis of dengue relies on clinical evaluation combined with laboratory investigations. Key diagnostic insights include:

1. Common Laboratory Findings:

- Leukopenia (low white blood cell count)

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

- Hyponatremia (low sodium levels)

- Elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

- Normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

- Normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

2. Serological Testing:

- Dengue virus-specific IgM:

- Develops toward the end of the first week of illness.

- Becomes positive typically 4–5 days after symptom onset.

- Levels peak and persist for up to 12 weeks post-onset, although they may last longer in some cases.

- Neutralizing antibodies: Appear during recovery, indicating past infection.

3. Molecular Testing

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT):

- Techniques such as real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) and in situ hybridization are used to detect dengue virus RNA.

- Ideal for early detection during the viremic phase.

4. Fixed Tissue Specimen Analysis

Tissue-based tests:

- NAATs can detect viral RNA in tissue samples.

- Performed on biopsy or autopsy specimens to confirm the presence of dengue virus.

Clinical Phases of Dengue:

Dengue progresses through three distinct clinical phases: Febrile, Critical, and Convalescent, each with unique features and challenges.

1. Febrile Phase:

Duration: Typically lasts 2–7 days, with fever that can be biphasic.

Common Signs and Symptoms:

- Severe headache

- Retro-orbital eye pain

- Muscle, joint, and bone pain

- Rashes: Macular or maculopapular rash

- Minor hemorrhagic manifestations:

- Petechiae, ecchymosis, purpura

- Epistaxis, bleeding gums, hematuria

- Positive tourniquet test

- Facial erythema: Notable in some patients within the first 24–48 hours of fever onset.

Warning Signs of Severe Dengue:

- Persistent vomiting

- Severe abdominal pain

- Fluid accumulation

- Mucosal bleeding

- Difficulty breathing

- Lethargy or restlessness

- Postural hypotension

- Liver enlargement

- Hemoconcentration: Progressive increase in hematocrit.

2. Critical Phase:

- Onset: Begins at defervescence, lasting approximately 24–48 hours.

Key Features:

- Severe plasma leakage due to increased vascular permeability:

- Pleural effusions

- Ascites

- Hypoproteinemia

- Hemoconcentration

- Compensatory mechanisms may maintain circulation temporarily, but:

- Rapid systolic blood pressure decline leads to irreversible shock and possibly death.

- Severe hemorrhagic manifestations:

- Hematemesis, bloody stool, menorrhagia (prolonged shock increases risk).

- Rare complications:

- Hepatitis

- Myocarditis

- Pancreatitis

- Encephalitis

3. Convalescent Phase:

- Transition: Occurs as plasma leakage subsides and the patient’s overall condition improves.

Key Features:

- Stabilized hemodynamic status

- Diuresis

- Recovery in blood parameters:

- White blood cell count rises first, followed by platelet count recovery.

- Rash characteristics:

- Desquamation (peeling skin)

- Pruritus (itchiness)

Dengue During Pregnancy:

Dengue infection during pregnancy presents unique challenges and risks due to limited data and potential maternal-fetal complications.

1. Perinatal Transmission:

- Dengue virus can be transmitted perinatally.

- Maternal infection during the peripartum period increases the likelihood of symptomatic infection in the newborn.

2. Clinical Features in Perinatally Infected Neonates:

- Based on case literature (41 perinatal transmission cases):

- Thrombocytopenia: Observed in all cases.

- Plasma leakage: Evidenced by ascites or pleural effusions in most cases.

- Fever: Absent in only two cases.

- Hemorrhagic manifestations: Occurred in nearly 40% of cases.

- Hypotension: Reported in 1 in 4 cases.

- Neonates typically develop symptoms during the first week of life.

3. Role of Maternal Antibodies:

However, these antibodies may increase the risk of severe dengue in infants aged 6–12 months, as their protective effect wanes during this period.

Maternal IgG antibodies (from a prior dengue infection) transferred through the placenta can initially provide protection.

Treatment of Dengue:

Currently, there is no specific antiviral treatment for dengue fever. Management focuses on supportive care to alleviate symptoms and prevent complications.

1. General Supportive Care:

- Hydration: Patients should stay well-hydrated to prevent dehydration.

- Fever Management:

- Use acetaminophen for fever control.

- Avoid aspirin, aspirin-containing drugs, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., ibuprofen) due to their anticoagulant properties, which increase the risk of bleeding.

- Tepid sponge baths can help lower body temperature.

- Electrolyte Replacement: May be required in some cases.

2. Preventing Further Transmission:

- Febrile patients should avoid mosquito bites to reduce the risk of spreading the virus to others.

3. Management of Severe Dengue:

- Hospitalization:

- Patients with severe dengue should receive care in an intensive care unit (ICU) for close observation and frequent monitoring.

- Intravenous Fluids:

- Administered to manage plasma leakage and maintain hemodynamic stability.

- Blood transfusions may be necessary in cases of significant blood loss.

- Platelet Transfusions:

- Prophylactic platelet transfusions are not recommended as they may lead to fluid overload without providing clinical benefit.

- Corticosteroids:

- Not routinely recommended.

- Should only be considered for autoimmune-related complications such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) or immune thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP).

Dengue Vaccine

• A dengue vaccine is approved for use in children aged 9 to 16 years with laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and living in areas where dengue is endemic (common).

• A vaccine to prevent dengue (Dengvaxia®) is licensed and available in some countries for people aged 9 to 45 years.

• The World Health Organization recommends that the vaccine only be given to persons with confirmed previous dengue virus infection.

• The vaccine manufacturer, Sanofi Pasteur, announced in 2017 that people who receive the vaccine and have not been previously infected with a dengue virus may be at risk of developing severe dengue if they get dengue after being vaccinated.

Malaria

an acute febrile illness caused by Plasmodium parasites which are spread to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

It is preventable and curable.

Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk of malaria.

Infants and children under 5 years of age, pregnant women and patients with HIV/AIDS are at particular risk.

Other vulnerable groups include people entering areas with intense malaria transmission who have not acquired partial immunity from long exposure to the disease, or who are not taking chemopreventive therapies, such as migrants, mobile populations and travellers. partial immunity reduces the risk that malaria infection will cause severe disease.

For this reason, most malaria deaths in Africa occur in young children, whereas in areas with less transmission and low immunity, all age groups are at risk.

Epidemiology

• a life-threatening disease primarily found in tropical countries.

• a case of uncomplicated malaria can progress to a severe form of the disease, which is often fatal without treatment.

• Malaria is not contagious and cannot spread from one person to another; the disease is transmitted through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes.

• Five species of parasites can cause malaria in humans and 2 of these species – Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax – pose the greatest threat.

• There are over 400 different species of Anopheles mosquitoes and around 40, known as vector species, can transmit the disease.

• Malaria occurs primarily in tropical and subtropical countries.

• The vast majority of malaria cases and deaths are found in the WHO African Region, with nearly all cases caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite.

• This parasite is also dominant in other malaria hotspots, including the WHO regions of

South-East Asia, Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific. In the WHO Region of the Americas, the Plasmodium vivax parasite is predominant, causing 75% of malaria cases.

• The threat of malaria is highest in sub-Saharan Africa

Symptoms

• symptoms usually begin within 10–15 days after the bite from an infected mosquito.

• Fever, headache and chills are typically experienced, though these symptoms may be mild and difficult to recognize as malaria.

• partial immunity-no symptoms (asymptomatic infections).

• If Plasmodium falciparum malaria is not treated within 24 hours, the infection can progress to severe illness and death.

• Severe malaria can cause multi-organ failure in adults, while children frequently suffer from severe anaemia, respiratory distress or cerebral malaria.

• Human malaria caused by other Plasmodium species can cause significant illness and occasionally life-threatening disease.

• Symptoms of malaria include fever and flu-like illness, including shaking chills, headache, muscle aches, and tiredness.

• Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may also occur.

• Malaria may cause anemia and jaundice (yellow coloring of the skin and eyes) because of the loss of red blood cells.

• If not promptly treated, the infection can become severe and may cause kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma, and death

Diagnosis

• There are 2 main types of tests:

microscopic examination of blood smears

rapid diagnostic tests.

Malaria RDTs detect

specific antigens (proteins) produced by malaria parasites in the blood of infected individuals. Some RDTs can detect only one species (Plasmodium falciparum or P. vivax) while others detect multiple species

Prevention

• Malaria is a preventable disease.

• Vector control interventions.

• insecticide-treated nets, which prevent bites while people sleep and which kill mosquitoes as they try to feed, and indoor residual spraying, which is the application of an insecticide to surfaces

• Chemo preventive therapies and chemoprophylaxis.

• malaria chemopreventive therapies for people living in endemic areas include intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy, perennial malaria chemoprevention, seasonal malaria chemoprevention, post-discharge malaria chemoprevention, and intermittent preventive treatment of malaria for school-aged children.

• Chemoprophylaxis drugs are also given to travellers before entering an area where malaria is endemic and can be highly effective when combined with insecticide-treated nets.

Treatment

• Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the most effective antimalarial medicines and the mainstay of recommended treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria

• ACTs contain artemisinin extracted from the plant Artemisia annua and a partner drug. The role of the artemisinin compound is to reduce the number of parasites during the first 3 days of treatment, while the role of the partner drug is to eliminate the remaining parasites.

• WHO recommends that treatment should only be administered if a person tests positive for malaria.

• WHO is also concerned about more recent reports of drug-resistant malaria in Africa.

• To date, resistance has been documented in 3 of the 5 malaria species known to affect humans: P. falciparum, P. vivax, and P. malariae. However, nearly all patients infected with artemisinin-resistant parasites who are treated with an ACT are fully cured, provided the partner drug is highly efficacious.

Artesunate+Sulfad oxinePyrimethamine for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Falciparum Malaria (ASPF). ArtemetherLumefantrine Artemisin based combination therapy

Typhoid/Enteric Fever

Causedby salmonella typhi and paratyphi , Gram negative bacteria

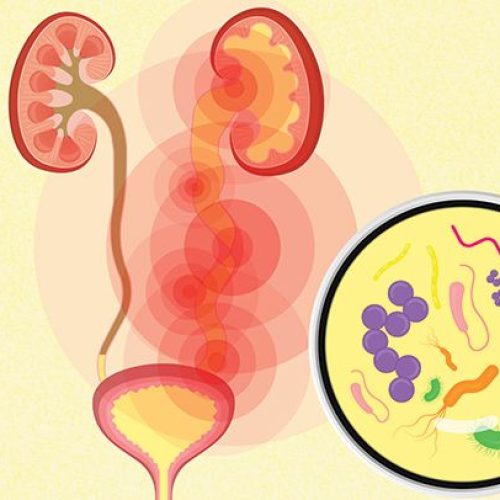

a life-threatening infection caused by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi.

Once ingested, they multiply and spread into the bloodstream.

increasing resistance to antibiotic treatment is making it easier for typhoid to spread in communities that lack access to safe drinking water or adequate sanitation.

Etiology

• Serious intestinal infection.

• Systemic disease of varying severity

• Higher risk of typhoid fever in countries or areas with low standards of hygiene and water supply facilities.

• The highest case fatality rates are reported in children <4 years

• Pollution of water sources may produce epidemics of typhoid fever

Symptoms

• Fever that starts low and increases daily, possibly reaching as high as 104.9 F

• Headache

• Weakness and fatigue • Muscle aches

• Sweating & Dry cough

• Loss of appetite and weight loss

• Abdominal pain

• Diarrhea or constipation

• Rash Later illness: If don’t treat

• Become delirious

• Lie motionless

• Exhausted with your eyes halfclosed (typhoid state) •life-threatening complications. In some people, signs and symptoms may return up to two

• Febrile illness 5-21 days after ingewsteioenksafter the fever has of contaminated food or water subsided.

Causes

• Oral transmission via contaminated food or beverages orsewagecontaminated water

• Hand-to-mouth transmission after using a contaminated toilet and neglecting hand hygiene

• Fecal-oral transmission route

• Shellfish taken from sewagepolluted areas

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Culture: Blood, intestinal secretions (vomitus or duodenal aspirate), bone marrowand stool culture.

Other nonspecific laboratory studies:

Most patients with typhoid fever are

• CBC — moderately anemic and increase WBC

• ESR– an elevated ESR, thrombocytopenia

• PT — elevated PT and aPTT

• Liver transaminase and serum bilirubin values usually rise.

• Mild hyponatremia and hypokalemia are common. 6

Widal Test

• an advanced way to check for antibodies that your body makes against the salmonella bacteria that causes typhoid fever. It looks for O and H antibodies in a patient’s sample blood (serum).

Complications

• Intestinal bleeding or holes intestinal bleeding or holes (perforations) in the intestine

• Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

• Other, less common complications

Myocarditis

Endocarditis

Pneumonia

Pancreatitis

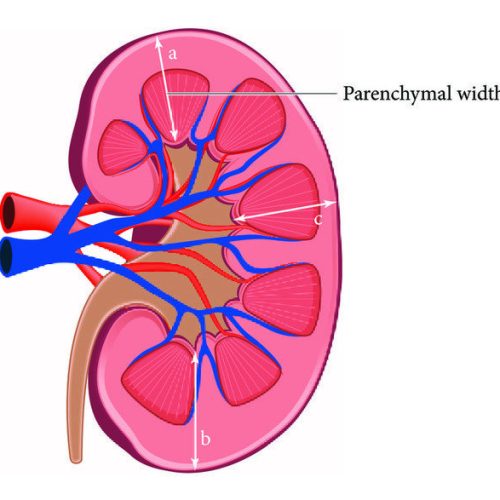

Kidney or bladder infections

Meningitis

Psychiatric problems, such as delirium, hallucinations

Treatment With Antibiotics:

• Azithromycin Adult 1g orally once then 0.5g orally daily OR 1g orally once daily for 7 days. Pediatric dose is 20 mg/kg orally once for 7 days.

• Ciprofloxacin 500-750 mg orally q12h or 400mg IV q12h

• Levofloxacin 500mg – 750 mg IV/PO once daily

• Bactrim DS (TMP-SMX) 160/800mg Q12H

• Ceftriaxone 1-2 grams IV q24h

• Cefexime 20mg/kg Q24Hr or divided Q12Hr

Corticosteroids:

• Used in severe Typhoid.

• Dexamethasone 3mg/kg IV over 30 minutes followed by dexamethasone 1 mg/kg every 6 hours for 8 doses.

Treatment With Antibiotic

Highly-resistant strains:

• Imipenem 0.5g-1gm IV every 6 hours (Range: 250-1000 mg q6-8h]

OR

• Meropenem 1 gram IV q8h

• Combination of azithromycin and fluoroquinolones is not recommended because it may cause QT prolongation and is relatively contraindicated.

Antibiotic Resistance In Current Scenario:

• Antibiotic resistance is a moving target.

• Reports are quickly outdated

• Surveys of resistance may have limited geographic scope.

Example in Pakistan:

Health officials in Pakistan reported an ongoing outbreak of XDR typhoid fever that began in Hyderabad in November 2016 and spread to the city of Karachi and to multiple districts, and several deaths have been reported. During 2016-18, 8188 cases of typhoid were reported out of which 64% were XDR typhoid.

Antibiotic Resistance In Current Scenario:

For MDR Typhoid

• Oral Cefixime

• IV Ceftriaxone for severe cases For XDR Typhoid

• Azithromycin or Carbapenems are indicated (based on susceptibility testing).

• Carbapenems should be used for patients with suspected severe or complicated typhoid.

Prevention

• Food, Water & Hygiene

• Limit consuming raw, unwashed/unhygienic food and water

• Frequent hand washing

• Chlorine tablets to purify water

Vaccine:

• Who should get typhoid vaccine and when?

• Travelers to parts of the world where typhoid is common.

• People in close contact with a typhoid carrier.

• Laboratory workers who work with Salmonella Typhi

Prevention

Vaccine/Role of Immunization

Typhoid vaccines protect 50%–80% of recipients and should be offered to patients with increased risk of exposure.

•Vi Capsular Polysaccharide Typhoid vaccine (Typbar) Single 0.5 mL intramuscular injection.

A booster dose is may be given after 3 years

•Oral Ty21a live-attenuated vaccine